Initiation into Self-realization

Kiriti Sengupta

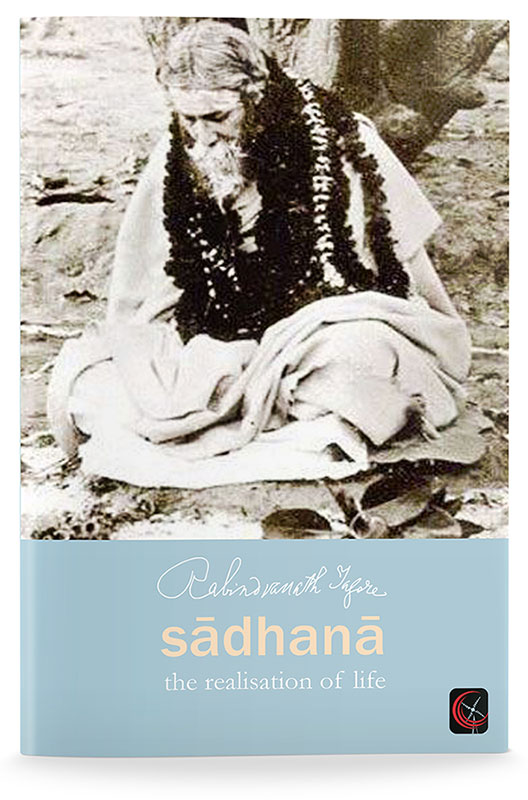

A preamble excerpted with permission from Sadhana: the realisations of life by Rabindranath Tagore, published by CLASSIX (an imprint of Hawakal Publishers)

I was pleasantly surprised as a few weeks ago, Bitan Chakraborty expressed his keen interest to re-introduce Rabindranath Tagore’s Sādhanā: the realisation of life through CLASSIX. He wanted to disseminate Tagore’s invaluable teachings that, he thought, the world needed to acquire anew. However, I was left bemused when Bitan solicited from me a brief proem to the collection of essays, first published in London (October 1913) and then in the United States by The Macmillian Company, New York. The following few days were challenging: what can I add to this accomplished volume of essays that, as Tagore reveals in his preface, are “ideas which have been culled from several of the Bengali discourses which I am in the habit of giving to my students in my school at Bolpur in Bengal?”

My approach to writing the preamble began with a Facebook update wherein I inquired:

Rabindranath Tagore was a disciplined scholar of ancient scriptural texts. He studied the Upanishads, the Geeta, the Patanjali Yogasutras, among other religious discourses. However, very little is known about the practice Tagore followed. For example, was he a supporter of the Tantric ways of realizing God? Or was Tagore an adjutant of Raj Yoga? Several researchers have investigated Tagore’s spirituality, mysticism, or understanding of humanity in his works, especially lyrics and poetry. A lot is written about his seminal work Gitanjali. Are you aware of any survey that deals with Tagore’s faith in religious practices other than his familial connection with the Adi Brahmo Samaj?

Among barely a handful of comments that arrived on my timeline, two deserve mention. First, Sreemati Mukherjee (Professor in the Department of Performing Arts, Presidency University, Calcutta) shared her insightful take. She wrote:

Sound was critical to Rabindranath. I remember reading in Jiban Smriti that when he was getting ready for his upanayana, his father had created a liturgy for him to learn. He referred with reverence to the practice of the Gayatri Mantra. Despite being Brahmo, Debendranath Tagore did not give up the course of upanayana—the caste privilege must have mattered to him. Debendranath paid for all Rabindranath’s social responsibilities, like the marriage expenses of Rabindranath’s daughters. Again, Rabindranath loved the sindoor and appreciated women wearing it. His life practices were determined by the aesthetic implications of reeti and rivaj.

Debanjan Bhowmik (Assistant Professor in the Department of Electrical Engineering, Indian Institute of Technology, Delhi) emphasized his faith:

Based on the understanding I developed through my readings of Gitanjali and Tagore’s other works in that genre, I would say he probably followed the path of Bhakti Yoga and Sufism to some degree, in the lines of Kabir, Amir Khusrau, or the Bauls. I don’t know whether he openly talked or wrote about that influence. Still, he wrote and published the English rendering of Kabir’s poetry (Songs of Kabir, translated by Rabindranath Tagore, 1915) when he released Gitanjali. I feel Kabir’s works and Gitanjali have a similar essence: finding the divine through loving the beloved, Nature, and simple things of life. But of course, Tagore must have taken an interest in other modes of spiritual practice outside Bhakti and Sufi; to me, he seems to have lived the life of a balanced and dynamic person, curious about many paths and ideologies and yet not particularly biased on a specific one.

The word Sādhanā bears a spiritual connotation that refers to an austere practice leading one to realize oneself. Sādhanā is intrinsic to Yoga as propagated by ancient scriptures and the sages and monks of all ages. However, not much is known about Tagore’s initiation into Sanatana Dharma, otherwise called the eternal religion.

Looking back at Debanjan’s initial few words: “Based on the understanding I developed through my readings…” — isn’t this the most standard way of exploring an author’s work? The author’s psyche? Categorizing Tagore as just another author is a grave injustice to his illustrious life and body of work. He played various roles—a poet, novelist, short story writer, dramatist, lyricist, educationist, environmentalist, and more. However, in all that he did, he sought the truth. Tagore was a seeker, and a tenacious one at that.

Let me probe his credos: on December 22, 1901, Tagore established a school for children in Bhubandanga, Bolpur. It’s called Brahmacharyasrama, also spelled as Brahmacharya Ashram. Later, the school was named Patha-Bhavana. Post-independence, the school flourished as Visva-Bharati. The university website (visvabharati.ac.in) claims:

Classes were held in open air in the shade of trees where man and nature entered into an immediate harmonious relationship. Teachers and students shared the single integral socio-cultural life. The curriculum had music, painting, dramatic performances, and other performative practices. Beyond the accepted limits of intellectual and academic pursuits, opportunities were created for invigorating and sustaining the manifold faculties of the human personality.

I’ll explore excerpts from a few letters Tagore wrote to Bhupendranath Sanyal during his tenure as a teacher or Adhyaksha in Brahmacharya Ashram. But, before that, let’s look at how Supriya Roy introduces Sanyal (referred to as Sanyal Mahasaya by his followers later in his life) in her Makers of a Mission (Santiniketan: Rabindra-Bhavana, 2001):

Although Rabindranath started his school based on the ideal of the ancient hermitage schools, his creativity did not allow him to adhere strictly to these lines. Bhupendranath Sanyal was one of those teachers who preferred the older ideal. Before coming to Santiniketan, he ran a store for Swadeshi goods. Once on a personal visit to Santiniketan, he met Rabindranath, who had already heard about this upright man full of idealism. Rabindranath requested him to join the school, and in 1903, just after the Autumn break, Bhupendranath joined the school. He was a loving teacher and took care of the children. He would nurse a sick child so tenderly that those looked after by him remembered him for it. When Mohit Sen had to leave the asrama due to ill-health, Rabindranath asked Bhupendranath to take charge as Adhyaksha.

Supriya Roy further notes, “Bhupendranath was in Santiniketan for about seven years….”

In one of his letters (2 January 1908) to Bhupendranath Sanyal, Tagore alerted:

Our school has daily chores, teaching, cultural events, arguments on scriptural texts, etc. But, where is He? The one who is the source of all Rasa? It isn’t compulsory to derive Rasa; we can work even without it. However, work isn’t the only motto. Exploring Rasa delights us. All enterprises come full circle when they bring happiness. When will that joy enlighten our students and teachers, at work and at leisure? It’s indeed meaningless to focus on our works with no attention to the results. Bhupen-babu, don’t let your mind become dry in your daily works. Let it instead sink in the boundless ocean of the world and beyond. Only then will you become free of regrets from worldly hindrance and loss. You will then feel joyous. There lies the beauty of life. And barring it, there is no prosperity.

In another letter (6 January 1908) to Sanyal, Tagore expressed his trust:

Had I succeeded in bringing a devout person amidst the teachers, I would have been thankful. There are plenty of teachers; they work to meet personal needs. I just hope they don’t impede the overall welfare of the school. God-realized souls are rare. Won’t we have the believers? We want the truth; we solicit God. That’s enough — not only for the students but also for us — for our spiritual growth. I’m so happy to have you. Whenever I think about the school, I look for you. You have been instrumental in making me inquisitive about God. Now, my curiosity is even more robust, for you seek Him too.

The following letter (21 April 1903) substantially augments Tagore’s faith in Sanyal:

I have long-nurtured a desire. I want to travel with you to several parts of India, even abroad, if possible. As I read your letter, I think my wish won’t be wasted. This way, I would like to conclude my worldly journey if I can secure your companionship. I didn’t write much about it in my last letter to you. But now that I’ve your support, I’m speaking my mind. I don’t want to get bound with any work. It’s imperative to come out of my family life. However, it will be improper to detach me from all auspicious activities. So, I need to fill my mind—whatever I can gain from traveling around. I will carry back home for my tender children like the girls frequenting the ghat to fetch water in pots to serve their families. But this seems to be an implausible proposition. So, I will instead saturate my mind while standing at the shore of the ocean of the truth. Whom shall I associate myself with reaching the goal if not you? I won’t force you, but if I’m benefited, you too will be blessed. One who is starving demands food out of acute hunger. There is this intense demand. How can you remain idle if you genuinely understand my need?

These letters offer significant insights: although Tagore was a follower of Adi Brahmo Samaj (a sect that believed in infinite singularity and denounced idol-worship and polytheism), his was an endless quest for God-realization. Second, his trust in Bhupendranath Sanyal went beyond the traditional alliance of employer and employee. Tagore looked up to Sanyal as his mentor—as a Master who inspired much interest in spirituality. Moreover, both Tagore and Sanyal were dedicated to day-to-day work; the former ensured the latter didn’t lose focus on his final goal of understanding the truth burdened with an unnecessary workload.

No wonder Tagore was formally initiated into Kriyayoga by Bhupendranath Sanyal at the age of 78. Prof. Haraprasad Ray, in his book, Kriya Yogi Bhupendranath Sanyal O Rabindranath (Howrah: Prachi Publications, 2012), reveals that Sanyal was accompanied by another yogi, Buddhadeb Bose. Both of them taught Tagore the intricate details and exercises of this stoic way to self-realization.

In his book, Prof. Ray also described when Tagore expressed his wish to Sanyal to meet an authentic Sadhu as they went out to Kashi (Varanasi). Sanyal took him to the Ranaghat premises to visit Krishnaram, one of the exalted disciples of Yogiraj Lahiri Mahasaya.

It is understood that there was no rift in their relationship even after Sanyal left the Brahmacharya Ashram. It is noteworthy that other than being the spiritual guide of Tagore, Sanyal also helped the school as he roped in Pandit Bidhushekhar Shastri (1905) and later, Pandit Kshitimohan Sen (1908). They elevated the teaching standard and brought more students and thus eased the prevailing financial crunch.

Tagore wrote in his preface to Sādhanā, “All the great utterances of man have to be judged not by the letter but by the spirit.” As readers peruse the following chapters, I hope they will grasp that apart from the sacred Indian scriptures, contemporaries, like Sanyal, helped Tagore become, as we understand him now, a sage thinker for all time.

References:

- Sādhanā: the realisation of life by Rabindranath Tagore

- Makers of a Mission by Supriya Roy

- Kriya Yogi Bhupendranath Sanyal O Rabindranath by Haraprasad Ray

Note: Sengupta has translated Tagore’s letters to Bhupendranath Sanyal, originally written in Bengali.

Leave a Reply